Wernher Von Braun on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Wernher Magnus Maximilian Freiherr von Braun ( , ; 23 March 191216 June 1977) was a German and American

The world's first large-scale experimental rocket program was

The world's first large-scale experimental rocket program was

In 1933, von Braun was working on his creative doctorate when the Nazi Party came to power in a coalition government in Germany; rocketry was almost immediately moved onto the national agenda. An artillery captain,

In 1933, von Braun was working on his creative doctorate when the Nazi Party came to power in a coalition government in Germany; rocketry was almost immediately moved onto the national agenda. An artillery captain,  On 22 December 1942,

On 22 December 1942,

In June 1937, at

In June 1937, at

The

The

On 20 June 1945,

On 20 June 1945,

''Red Moon Rising: Sputnik and the Hidden Rivalries That Ignited the Space Age''

pages 84–92, Henry Holt, New York His chief design engineer Walther Reidel became the subject of a December 1946 article "German Scientist Says American Cooking Tasteless; Dislikes Rubberized Chicken", exposing the presence of von Braun's team in the country and drawing criticism from While at Fort Bliss, they trained military, industrial, and university personnel in the intricacies of rockets and guided missiles. As part of the

While at Fort Bliss, they trained military, industrial, and university personnel in the intricacies of rockets and guided missiles. As part of the

In 1952, von Braun first published his concept of a crewed

In 1952, von Braun first published his concept of a crewed  At this time, von Braun also worked out preliminary concepts for a

At this time, von Braun also worked out preliminary concepts for a

"Rocket Man"

''

The

The  The Marshall Center's first major program was the development of

The Marshall Center's first major program was the development of  Von Braun also developed the idea of a Space Camp that would train children in fields of science and space technologies, as well as help their mental development much the same way sports camps aim at improving physical development.

Von Braun also developed the idea of a Space Camp that would train children in fields of science and space technologies, as well as help their mental development much the same way sports camps aim at improving physical development.

Von Braun had a charismatic personality and was known as a ladies' man. As a student in Berlin, he would often be seen in the evenings in the company of two girlfriends at once. He later had a succession of affairs within the secretarial and computer pool at Peenemünde.

In January 1943, von Braun became engaged to Dorothee Brill, a physical education teacher in Berlin, and he sought permission to marry from the

Von Braun had a charismatic personality and was known as a ladies' man. As a student in Berlin, he would often be seen in the evenings in the company of two girlfriends at once. He later had a succession of affairs within the secretarial and computer pool at Peenemünde.

In January 1943, von Braun became engaged to Dorothee Brill, a physical education teacher in Berlin, and he sought permission to marry from the

In 1973, von Braun was diagnosed with kidney cancer during a routine medical examination. However, he continued to work unrestrained for a number of years. In January 1977, then very ill, he resigned from Fairchild Industries. Later in 1977, President

In 1973, von Braun was diagnosed with kidney cancer during a routine medical examination. However, he continued to work unrestrained for a number of years. In January 1977, then very ill, he resigned from Fairchild Industries. Later in 1977, President

* Apollo program director

* Apollo program director

Wernher von Braun – Rocket Man for War and Peace

' - A three part

documentary – in English – from the German International channel DW-TV. Original German versio

''Wernher von Braun – Der Mann für die Wunderwaffen''

by the Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk. Played by Ludwig Blochberger. *''American Genius'' television series (2015): ''Space Race'' (Season 1, episode 5) - von Braun played by Corey Maher. *''Timeless (TV series), Timeless'' television series (2016): ''Party at Castle Varlar'' (Season 1, episode 4) – von Braun played by Christian Oliver. *''Project Blue Book (TV series), Project Blue Book'' television series (2019): "Operation Paperclip" (Season 1, episode 4) – von Braun played by Thomas Kretschmann. *''For All Mankind (TV series), For All Mankind'' television series (2019): "Red Moon" (Season 1, episode 1), "He Built the Saturn V" (Season 1, episode 2), "Home Again" (Season 1, episode 6) – von Braun played by Colm Feore. *Hunters (2020 TV series), ''Hunters'' (fictional web television series on Amazon Prime Video, 2020): "The Jewish Question" (Season 1, episode 8) – von Braun played by Victor Slezak. Several fictional characters have been modeled on von Braun: *''Dr. Strangelove, or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb'' (1964): Dr Strangelove is usually held to be based at least partly on von Braun. * ''Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny'' (2023): Dr. Jürgen Voller, the film's main antagonist, is inspired partly on von Braun according to his performer Mads Mikkelsen. In print media: *In Warren Ellis's graphic novel ''Ministry of Space'', von Braun is a supporting character, settling in Britain after World War II, and being essential for the realization of the British space program. *In Jonathan Hickman's comic book series ''The Manhattan Projects'', von Braun is a major character. In literature: *''The Good German'' by Joseph Kanon. Von Braun and other scientists are said to have been implicated in the use of slave labor at Peenemünde; their transfer to the U.S. forms part of the narrative. *''Space (Michener novel), Space'' by James Michener. Von Braun and other German scientists are brought to the U.S. and form a vital part of the U.S. efforts to reach space. *''Gravity's Rainbow'' by Thomas Pynchon. The novel involves British intelligence attempting to avert and predict V-2 rocket attacks. The work even includes a gyroscopic equation for the V2. The first portion of the novel, "Beyond The Zero", begins with a quotation from von Braun: "Nature does not know extinction; all it knows is transformation. Everything science has taught me, and continues to teach me, strengthens my belief in the continuity of our spiritual existence after death." *''V-S Day'' by Allen Steele is a 2014 alternate history novel in which the space race occurs during World War II between teams led by

Audiopodcast on Astrotalkuk.org

BBC journalist Reg Turnill talking in 2011 about his personal memories of and interviews with Dr Wernher von Braun.

– At the U.S. 44th Infantry Division website (archived)

Wernher von Braun page

– Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) History Office (archived)

Missile to Moon: PBS documentary about evolution of Huntsville to "Rocket City" and Werhner von Braun

– by Mike Wright, MSFC (archived)

Remembering Von Braun

– by Anthony Young – The Space Review Monday, 10 July 2006

60th anniversary digital reprinting of Colliers Space Series

''Houston Section of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics'' (archived) *iarchive:BraunWernherVon, CIA documents on Dr. Wernher von Braun on the Internet Archive

FBI Records: The Vault – Wernher VonBraun files

at vault.fbi.gov * *

Wernher von Braun Collection, The University of Alabama in Huntsville Archives and Special CollectionsDorette Schlidt Collection, The University of Alabama in Huntsville Archives and Special Collections

Files of Dorette Schlidt, Dr. Wernher von Braun's first secretary. {{DEFAULTSORT:Braun, Wernher von Wernher von Braun, 1912 births 1977 deaths 20th-century German physicists 20th-century American physicists 20th-century American engineers 20th-century American architects 20th-century American writers German aerospace engineers American aerospace engineers 20th-century German architects 20th-century German inventors American technology writers Apollo program Barons of Germany Nazi Party members Converts to Evangelicalism from Lutheranism Directors of the Marshall Space Flight Center Early spaceflight scientists ETH Zurich alumni Französisches Gymnasium Berlin alumni German emigrants to the United States German rocket scientists Humboldt University of Berlin alumni Knights Commander of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany Center Directors of NASA National Medal of Science laureates Operation Paperclip Peenemünde Army Research Center and Airfield People from Huntsville, Alabama People from the Province of Posen People from Piła County People with acquired American citizenship Architects in the Nazi Party Research and development in Nazi Germany Space advocates SS-Sturmbannführer Technical University of Berlin alumni Werner von Siemens Ring laureates V-weapons people Recipients of the Knights Cross of the War Merit Cross Recipients of the NASA Distinguished Service Medal Recipients of the President's Award for Distinguished Federal Civilian Service Deaths from cancer in Virginia Deaths from pancreatic cancer Burials at Ivy Hill Cemetery (Alexandria, Virginia) Members of the American Rocket Society

aerospace engineer

Aerospace engineering is the primary field of engineering concerned with the development of aircraft and spacecraft. It has two major and overlapping branches: aeronautical engineering and astronautical engineering. Avionics engineering is s ...

and space architect. He was a member of the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

and Allgemeine SS

The ''Allgemeine SS'' (; "General SS") was a major branch of the ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) paramilitary forces of Nazi Germany; it was managed by the SS Main Office (''SS-Hauptamt''). The ''Allgemeine SS'' was officially established in the autumn ...

, as well as the leading figure in the development of rocket technology in Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and later a pioneer of rocket and space technology in the United States.

As a young man, von Braun worked in Nazi Germany's rocket development program. He helped design and co-developed the V-2 rocket

The V-2 (german: Vergeltungswaffe 2, lit=Retaliation Weapon 2), with the technical name ''Aggregat 4'' (A-4), was the world’s first long-range guided ballistic missile. The missile, powered by a liquid-propellant rocket engine, was develop ...

at Peenemünde during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

. Following the war, he was secretly moved to the United States, along with about 1,600 other German scientists, engineers, and technicians, as part of Operation Paperclip

Operation Paperclip was a secret United States intelligence program in which more than 1,600 German scientists, engineers, and technicians were taken from the former Nazi Germany to the U.S. for government employment after the end of World War ...

. He worked for the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

on an intermediate-range ballistic missile

An intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) is a ballistic missile with a range of 3,000–5,500 km (1,864–3,418 miles), between a medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM) and an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM). Classifying ...

program, and he developed the rockets that launched the United States' first space satellite Explorer 1

Explorer 1 was the first satellite launched by the United States in 1958 and was part of the U.S. participation in the International Geophysical Year (IGY). The mission followed the first two satellites the previous year; the Soviet Union's S ...

in 1958. He worked with Walt Disney

Walter Elias Disney (; December 5, 1901December 15, 1966) was an American animator, film producer and entrepreneur. A pioneer of the American animation industry, he introduced several developments in the production of cartoons. As a film p ...

on a series of films, which popularized the idea of human space travel in the US and beyond between 1955 and 1957.

In 1960, his group was assimilated into NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeedin ...

, where he served as director of the newly formed Marshall Space Flight Center

The George C. Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC), located in Redstone Arsenal, Alabama (Huntsville postal address), is the U.S. government's civilian rocketry and spacecraft propulsion research center. As the largest NASA center, MSFC's firs ...

and as the chief architect of the Saturn V

Saturn V is a retired American super heavy-lift launch vehicle developed by NASA under the Apollo program for human exploration of the Moon. The rocket was human-rated, with multistage rocket, three stages, and powered with liquid-propellant r ...

super heavy-lift launch vehicle

A super heavy-lift launch vehicle can lift to low Earth orbit more than by United States (NASA) classification or by Russian classification. It is the most capable launch vehicle classification by mass to orbit, exceeding that of the heavy-lif ...

that propelled the Apollo spacecraft

The Apollo spacecraft was composed of three parts designed to accomplish the American Apollo program's goal of landing astronauts on the Moon by the end of the 1960s and returning them safely to Earth. The expendable (single-use) spacecraft ...

to the Moon. In 1967, von Braun was inducted into the National Academy of Engineering

The National Academy of Engineering (NAE) is an American nonprofit, non-governmental organization. The National Academy of Engineering is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of ...

, and in 1975, he received the National Medal of Science

The National Medal of Science is an honor bestowed by the President of the United States to individuals in science and engineering who have made important contributions to the advancement of knowledge in the fields of behavioral and social scienc ...

.

Von Braun is widely seen as the "father of space travel", the "father of rocket science" or the "father of the American lunar program". He advocated a human mission to Mars

The idea of sending humans to Mars has been the subject of aerospace engineering and scientific studies since the late 1940s as part of the broader exploration of Mars. Some have also considered exploring the Martian moons of Phobos (moon), Phob ...

.

Early life

Wernher von Braun was born on 23 March 1912, in the small town of Wirsitz in theProvince of Posen

The Province of Posen (german: Provinz Posen, pl, Prowincja Poznańska) was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1848 to 1920. Posen was established in 1848 following the Greater Poland Uprising as a successor to the Grand Duchy of Posen, w ...

, Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Re ...

, then German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

and now Poland.

His father, Magnus Freiherr von Braun (1878–1972), was a civil servant and conservative politician; he served as Minister of Agriculture in the federal government during the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is al ...

. His mother, Emmy von Quistorp (1886–1959), traced her ancestry through both parents to medieval European royalty

Royalty may refer to:

* Any individual monarch, such as a king, queen, emperor, empress, etc.

* Royal family, the immediate family of a king or queen regnant, and sometimes his or her extended family

* Royalty payment for use of such things as int ...

and was a descendant of Philip III of France

Philip III (1 May 1245 – 5 October 1285), called the Bold (french: le Hardi), was King of France from 1270 until his death in 1285. His father, Louis IX, died in Tunis during the Eighth Crusade. Philip, who was accompanying him, returned ...

, Valdemar I of Denmark

Valdemar I (14 January 1131 – 12 May 1182), also known as Valdemar the Great ( da, Valdemar den Store), was King of Denmark from 1154 until his death in 1182. The reign of King Valdemar I saw the rise of Denmark, which reached its medieval zen ...

, Robert III of Scotland

Robert III (c. 13374 April 1406), born John Stewart, was King of Scots from 1390 to his death in 1406. He was also High Steward of Scotland from 1371 to 1390 and held the titles of Earl of Atholl (1367–1390) and Earl of Carrick (1368– ...

, and Edward III of England

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring ro ...

. Wernher had an older brother, the West German diplomat Sigismund von Braun

Sigismund Freiherr von Braun (14 April 1911 – 13 July 1998) was a German diplomat and Secretary of State in the Foreign Office (1970–1972).

Biography

Sigismund von Braun was born in Berlin- Zehlendorf in 1911, the eldest son of the East Pru ...

, who served as Secretary of State in the Foreign Office in the 1970s, and a younger brother, Magnus von Braun

Magnus "Mac" Freiherr von Braun (10 May 1919 – 21 June 2003) was a German chemical engineer, Luftwaffe aviator, rocket scientist and business executive. In his 20s he worked as a rocket scientist at Peenemünde and the Mittelwerk.

At age 26, ...

, who was a rocket scientist and later a senior executive with Chrysler

Stellantis North America (officially FCA US and formerly Chrysler ()) is one of the " Big Three" automobile manufacturers in the United States, headquartered in Auburn Hills, Michigan. It is the American subsidiary of the multinational automoti ...

.

The family moved to Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

, Brandenburg

Brandenburg (; nds, Brannenborg; dsb, Bramborska ) is a states of Germany, state in the northeast of Germany bordering the states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony, as well as the country of Poland. With an ar ...

, in 1915, where his father worked at the Ministry of the Interior. After Wernher's Confirmation

In Christian denominations that practice infant baptism, confirmation is seen as the sealing of the covenant created in baptism. Those being confirmed are known as confirmands. For adults, it is an affirmation of belief. It involves laying on ...

, his mother gave him a telescope

A telescope is a device used to observe distant objects by their emission, absorption, or reflection of electromagnetic radiation. Originally meaning only an optical instrument using lenses, curved mirrors, or a combination of both to observe ...

, and he developed a passion for astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

. Von Braun learned to play both the cello and the piano at an early age and at one time wanted to become a composer. He took lessons from the composer Paul Hindemith

Paul Hindemith (; 16 November 189528 December 1963) was a German composer, music theorist, teacher, violist and conductor. He founded the Amar Quartet in 1921, touring extensively in Europe. As a composer, he became a major advocate of the ''Ne ...

. The few pieces of Wernher's youthful compositions that exist are reminiscent of Hindemith's style. He could play piano pieces of Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classical ...

and Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque period. He is known for his orchestral music such as the '' Brandenburg Concertos''; instrumental compositions such as the Cello Suites; keyboard w ...

from memory. Beginning in 1925, Wernher attended a boarding school at Ettersburg

Ettersburg is a municipality in the Weimarer Land district of Thuringia, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, ...

Castle near Weimar

Weimar is a city in the state of Thuringia, Germany. It is located in Central Germany between Erfurt in the west and Jena in the east, approximately southwest of Leipzig, north of Nuremberg and west of Dresden. Together with the neighbouri ...

, Free State of Thuringia

Thuringia (; german: Thüringen ), officially the Free State of Thuringia ( ), is a state of central Germany, covering , the sixth smallest of the sixteen German states. It has a population of about 2.1 million.

Erfurt is the capital and larg ...

, where he did not do well in physics and mathematics. There he acquired a copy of ''Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen'' (1923, ''By Rocket into Planetary Space'') by rocket pioneer Hermann Oberth

Hermann Julius Oberth (; 25 June 1894 – 28 December 1989) was an Austro-Hungarian-born German physicist and engineer. He is considered one of the founding fathers of rocketry and astronautics, along with Robert Esnault-Pelterie, Konstantin Ts ...

. In 1928, his parents moved him to the Hermann-Lietz-Internat (also a residential school) on the East Frisia

East Frisia or East Friesland (german: Ostfriesland; ; stq, Aastfräislound) is a historic region in the northwest of Lower Saxony, Germany. It is primarily located on the western half of the East Frisian peninsula, to the east of West Frisia ...

n North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

island of Spiekeroog

Spiekeroog is one of the East Frisian Islands, off the North Sea coast of Germany. It is situated between Langeoog to its west, and Wangerooge to its east. The island belongs to the district of Wittmund, in Lower Saxony in Germany. The only vi ...

. Space travel had always fascinated Wernher, and from then on he applied himself to physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

and mathematics to pursue his interest in rocket engineering.

The world's first large-scale experimental rocket program was

The world's first large-scale experimental rocket program was Opel RAK

Opel-RAK were a series of rocket vehicles produced by German automobile manufacturer Fritz von Opel, of the Opel car company, in association with others, including Max Valier, Julius Hatry, and Friedrich Wilhelm Sander. Opel RAK is generally con ...

under the leadership of Fritz von Opel

Fritz Adam Hermann von Opel (4 May 1899 – 8 April 1971) was a German rocket technology pioneer and automotive executive, nicknamed "Rocket-Fritz". He is remembered mostly for his spectacular demonstrations of rocket propulsion that earned him an ...

and Max Valier

Max Valier (9 February 1895 – 17 May 1930) was an Austrian rocketry pioneer. He was a leading figure in the world's first large-scale rocket program, Opel-RAK, and helped found the German ''Verein für Raumschiffahrt'' (VfR – "Spacefligh ...

during the late 1920s leading to the first manned rocket cars and rocket planes, which paved the way for the Nazi era V2 program and US and Soviet activities from 1950 onwards.The Opel RAK program and the spectacular public demonstrations of ground and air vehicles drew large crowds, as well as caused global public excitement as so-called "Rocket Rumble" and had a large long-lasting impact on later spaceflight pioneers, in particular on Wernher von Braun. Sixteen year old Wernher was so enthusiastic about the public Opel RAK demonstrations, that he constructed his own homemade rocket car, nearly killing himself in the process. and causing a major disruption in a crowded street by detonating the toy wagon to which he had attached fireworks. He was taken into custody by the local police until his father came to get him. The Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

put an end to the Opel RAK program and Fritz von Opel left Germany in 1930, emigrating first to the US, later to France and Switzerland. After the break-up of Opel-RAK program, Valier eventually was killed while experimenting with liquid-fueled rockets as means of propulsion in mid-1930, and is considered the first fatality of the dawning space age.

In 1930, von Braun attended the Technische Hochschule Berlin

The Technical University of Berlin (official name both in English and german: link=no, Technische Universität Berlin, also known as TU Berlin and Berlin Institute of Technology) is a public research university located in Berlin, Germany. It was ...

, where he joined the ''Spaceflight Society'' (''Verein für Raumschiffahrt

''Verein'' is a German word, sometimes translated as ''union'', ''club'' or ''association'', and may refer to:

* ''Eingetragener Verein'' (e. V.), a registered voluntary association under German law

* Swiss Verein, a voluntary association under Sw ...

'' or "VfR"), co-founded by Valier, and worked with Willy Ley

Willy or Willie is a masculine, male given name, often a diminutive form of William or Wilhelm, and occasionally a nickname. It may refer to:

People Given name or nickname

* Willie Aames (born 1960), American actor, television director, and scree ...

in his liquid-fueled rocket motor tests in conjunction with others such as Rolf Engel Rolf is a male given name and a surname. It originates in the Germanic name ''Hrolf'', itself a contraction of ''Hrodwulf'' ( Rudolf), a conjunction of the stem words ''hrod'' ("renown") + ''wulf'' ("wolf"). The Old Norse cognate is ''Hrólfr''. A ...

, Rudolf Nebel

Rudolf Nebel (21 March 1894 – 18 September 1978) was a spaceflight advocate active in Germany's amateur rocket group, the ''Verein für Raumschiffahrt'' (VfR – "Spaceflight Society") in the 1930s and in rebuilding German rocketry following Wor ...

, Hermann Oberth

Hermann Julius Oberth (; 25 June 1894 – 28 December 1989) was an Austro-Hungarian-born German physicist and engineer. He is considered one of the founding fathers of rocketry and astronautics, along with Robert Esnault-Pelterie, Konstantin Ts ...

or Paul Ehmayr. In spring 1932, he graduated with a diploma in mechanical engineering. His early exposure to rocketry convinced him that the exploration of space would require far more than applications of the current engineering technology. Wanting to learn more about physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

, chemistry

Chemistry is the science, scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a natural science that covers the Chemical element, elements that make up matter to the chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules and ions ...

, and astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

, von Braun entered the Friedrich-Wilhelm University of Berlin for doctoral studies and graduated with a doctorate in physics in 1934. He also studied at ETH Zürich

(colloquially)

, former_name = eidgenössische polytechnische Schule

, image = ETHZ.JPG

, image_size =

, established =

, type = Public

, budget = CHF 1.896 billion (2021)

, rector = Günther Dissertori

, president = Joël Mesot

, ac ...

for a term from June to October 1931.

Career in Germany

In 1930, von Braun attended a presentation given byAuguste Piccard

Auguste Antoine Piccard (28 January 1884 – 24 March 1962) was a Switzerland, Swiss physicist, inventor and explorer known for his record-breaking Gas balloon, hydrogen balloon flights, with which he studied the Earth's upper atmosphere. Picca ...

. After the talk, the young student approached the famous pioneer of high-altitude balloon flight, and stated to him: "You know, I plan on traveling to the Moon at some time." Piccard is said to have responded with encouraging words.

Von Braun was greatly influenced by Oberth, of whom he said:

According to historian Norman Davies

Ivor Norman Richard Davies (born 8 June 1939) is a Welsh-Polish historian, known for his publications on the history of Europe, Poland and the United Kingdom. He has a special interest in Central and Eastern Europe and is UNESCO Professor at ...

, von Braun was able to pursue a career as a rocket scientist in Germany due to a "curious oversight" in the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

which did not include rocketry in its list of weapons forbidden to Germany.

Involvement with the Nazi regime

Nazi Party membership

Von Braun had an ambivalent and complex relationship withNazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

. He applied for membership of the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

on 12 November 1937, and was issued membership number 5,738,692.

Michael J. Neufeld

Michael J. Neufeld is a historian and author. He chaired the Space History Division at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum from 2007 to 2011, and continues to be a curator there.

Biography

Neufeld was born in Edmonton, Alberta, in 19 ...

, an author of aerospace history and chief of the Space History Division at the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum

The National Air and Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institution, also called the Air and Space Museum, is a museum in Washington, D.C., in the United States.

Established in 1946 as the National Air Museum, it opened its main building on the Nat ...

, wrote that ten years after von Braun obtained his Nazi Party membership, he signed an affidavit for the U.S. Army, though he stated the incorrect year:

In 1939, I was officially demanded to join the National Socialist Party. At this time I was already Technical Director at the Army Rocket Center at Peenemünde (Baltic Sea). The technical work carried out there had, in the meantime, attracted more and more attention in higher levels. Thus, my refusal to join the party would have meant that I would have to abandon the work of my life. Therefore, I decided to join. My membership in the party did not involve any political activity.It has not been ascertained whether von Braun's error with regard to the year was deliberate or a simple mistake. Neufeld further wrote:

Von Braun, like other Peenemünders, was assigned to the local group in Karlshagen; there is no evidence that he did more than send in his monthly dues. But he is seen in some photographs with the party's swastika pin in his lapel – it was politically useful to demonstrate his membership.Von Braun's later attitude toward the National Socialist regime of the late 1930s and early 1940s was complex. He said that he had been so influenced by the early Nazi promise of release from the post–World War I economic effects, that his patriotic feelings had increased. In a 1952 memoir article he admitted that, at that time, he "fared relatively rather well under

totalitarianism

Totalitarianism is a form of government and a political system that prohibits all opposition parties, outlaws individual and group opposition to the state and its claims, and exercises an extremely high if not complete degree of control and reg ...

". Yet, he also wrote that "to us, Hitler was still only a pompous fool with a Charlie Chaplin

Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin Jr. (16 April 188925 December 1977) was an English comic actor, filmmaker, and composer who rose to fame in the era of silent film. He became a worldwide icon through his screen persona, the Tramp, and is consider ...

moustache" and that he perceived him as "another Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

" who was "wholly without scruples, a godless man who thought himself the only god".

Later examination of Von Braun’s background, conducted by the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation, suggests that his background check file contained no derogatory information pertaining to his involvement in the party, but it was found that he had numerous letters of commendation for outstanding performance of duties during his time working under the Nazi party. Overall FBI conclusions point to Von Braun’s involvement in the Nazi Party to be purely for the furthering of his academic career, or out of fear of imprisonment or execution.

Membership in the Allgemeine-SS

Von Braun joined the SS horseback riding school on 1 November 1933 as an ''SS-Anwärter

''Anwärter'' is a German title which translates as “candidate” or "applicant". During the Nazi era, ''Anwärter/SS-Anwärter'' was used as a paramilitary rank by both the Nazi Party and the SS. Within the Nazi Party, an ''Anwärter'' was ...

''. He left the following year. In 1940, von Braun joined the SS and was given the rank of Untersturmführer

(, ; short: ''Ustuf'') was a paramilitary rank of the German ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) first created in July 1934. The rank can trace its origins to the older SA rank of ''Sturmführer'' which had existed since the founding of the SA in 1921. ...

in the Allgemeine-SS

The ''Allgemeine SS'' (; "General SS") was a major branch of the ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) paramilitary forces of Nazi Germany; it was managed by the SS Main Office (''SS-Hauptamt''). The ''Allgemeine SS'' was officially established in the autum ...

and issued membership number 185,068. In 1947, he gave the U.S. War Department this explanation:

When shown a picture of himself standing behind Himmler, von Braun claimed to have worn the SS uniform only that one time, but in 2002 a former SS officer at Peenemünde told the BBC that von Braun had regularly worn the SS uniform to official meetings. He began as an Untersturmführer (Second lieutenant) and was promoted three times by Himmler, the last time in June 1943 to SS-Sturmbannführer

__NOTOC__

''Sturmbannführer'' (; ) was a Nazi Party paramilitary rank equivalent to major that was used in several Nazi organizations, such as the SA, SS, and the NSFK. The rank originated from German shock troop units of the First World War ...

(Major). Von Braun later claimed that these were simply technical promotions received each year regularly by mail.Dr. Space, p. 35.

Work under Nazi regime

In 1933, von Braun was working on his creative doctorate when the Nazi Party came to power in a coalition government in Germany; rocketry was almost immediately moved onto the national agenda. An artillery captain,

In 1933, von Braun was working on his creative doctorate when the Nazi Party came to power in a coalition government in Germany; rocketry was almost immediately moved onto the national agenda. An artillery captain, Walter Dornberger

Major-General Dr. Walter Robert Dornberger (6 September 1895 – 26 June 1980) was a German Army artillery officer whose career spanned World War I and World War II. He was a leader of Nazi Germany's V-2 rocket programme and other projects a ...

, arranged an Ordnance

Ordnance may refer to:

Military and defense

*Materiel in military logistics, including weapons, ammunition, vehicles, and maintenance tools and equipment.

**The military branch responsible for supplying and developing these items, e.g., the Unit ...

Department research grant for von Braun, who then worked next to Dornberger's existing solid-fuel rocket test site at Kummersdorf

Kummersdorf is the name of an estate near Luckenwalde, around 25 km south of Berlin, in the Brandenburg region of Germany. Until 1945 Kummersdorf hosted the weapon office of the German Army which ran a development centre for future weapons as ...

.

In 1932, Von Braun received a Bachelor of Science Degree in Mechanical Engineering from the Institute of Technology in Berlin, Germany. During a period in 1931, Von Braun attended the Technical Institute in Switzerland. During this time in Switzerland, Von Braun assisted Professor Hermann Oberth in writing a book concerning the possibilities of creating and manufacturing liquid-propellant rockets. Shortly after this, Von Braun founded his own private rocket development business in Berlin, through which made the first rocket fired by gasoline and liquid oxygen.

In 1932, having caught wind of Von Braun’s rocket business, the German Army connected with Von Braun to pursue basic missile research and weather data experimentation. Von Braun said that the Germany Government financed the development of test stands and facilities for experimentation in Darmstadt, Germany. In 1939, Von Braun was appointed a technical advisor at Peenemunde Proving Ground on the Baltic Sea.

Von Braun was awarded a Doctorate of Philosophy

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, Ph.D., or DPhil; Latin: or ') is the most common degree at the highest academic level awarded following a course of study. PhDs are awarded for programs across the whole breadth of academic fields. Because it is a ...

in physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

(aerospace engineering

Aerospace engineering is the primary field of engineering concerned with the development of aircraft and spacecraft. It has two major and overlapping branches: aeronautical engineering and astronautical engineering. Avionics engineering is si ...

) on 27 July 1934, from the University of Berlin

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (german: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a German public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin. It was established by Frederick William III on the initiative o ...

for a thesis

A thesis ( : theses), or dissertation (abbreviated diss.), is a document submitted in support of candidature for an academic degree or professional qualification presenting the author's research and findings.International Standard ISO 7144: ...

entitled ''"About Combustion Tests"''; his doctoral supervisor was Erich Schumann

Erich Schumann (5 January 1898 – 25 April 1985) was a German physicist who specialized in acoustics and explosives, and had a penchant for music. He was a general officer in the army and a professor at the University of Berlin and the Technic ...

. However, this thesis was only the public part of von Braun's work. His actual full thesis, ''Construction, Theoretical, and Experimental Solution to the Problem of the Liquid Propellant Rocket'' (dated 16 April 1934) was kept classified by the German army, and was not published until 1960. By the end of 1934, his group had successfully launched two liquid fuel rockets that rose to heights of 2.2 and .

Von Braun continued his guided missile work throughout World War Two, and met with Adolf Hitler on several occasions, being formally decorated by Hitler twice, including being awarded the Iron Cross.

At the time, Germany was highly interested in American physicist Robert H. Goddard

Robert Hutchings Goddard (October 5, 1882 – August 10, 1945) was an American engineer, professor, physicist, and inventor who is credited with creating and building the world's first Liquid-propellant rocket, liquid-fueled rocket. ...

's research. Before 1939, German scientists occasionally contacted Goddard directly with technical questions. Von Braun used Goddard's plans from various journals and incorporated them into the building of the ''Aggregat

The Aggregat series (German for "Aggregate") was a set of ballistic missile designs developed in 1933–1945 by a research program of Nazi Germany's Armed Forces (Wehrmacht). Its greatest success was the A4, more commonly known as the V-2.

...

'' (A) series of rocket

A rocket (from it, rocchetto, , bobbin/spool) is a vehicle that uses jet propulsion to accelerate without using the surrounding air. A rocket engine produces thrust by reaction to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entirely fr ...

s. The first successful launch of an A-4 took place on 3 October 1942. The A-4 rocket would become well known as the V-2. In 1963, von Braun reflected on the history of rocketry, and said of Goddard's work: "His rockets ... may have been rather crude by present-day standards, but they blazed the trail and incorporated many features used in our most modern rockets and space vehicles."

Goddard confirmed his work was used by von Braun in 1944, shortly before the Nazis began firing V-2s at England. A V-2 crashed in Sweden and some parts were sent to an Annapolis lab where Goddard was doing research for the Navy. If this was the so-called Bäckebo Bomb, it had been procured by the British in exchange for Spitfire

The Supermarine Spitfire is a British single-seat fighter aircraft used by the Royal Air Force and other Allied countries before, during, and after World War II. Many variants of the Spitfire were built, from the Mk 1 to the Rolls-Royce Griff ...

s; Annapolis would have received some parts from them. Goddard is reported to have recognized components he had invented, and inferred that his brainchild had been turned into a weapon. Later, von Braun would comment: "I have very deep and sincere regret for the victims of the V-2 rockets, but there were victims on both sides ... A war is a war, and when my country is at war, my duty is to help win that war."

In response to Goddard's claims, von Braun said "at no time in Germany did I or any of my associates ever see a Goddard patent". This was independently confirmed. He wrote that claims about his lifting Goddard's work were the furthest from the truth, noting that Goddard's paper "A Method of Reaching Extreme Altitudes", which was studied by von Braun and Oberth, lacked the specificity of liquid-fuel experimentation with rockets. It was also confirmed that he was responsible for an estimated 20 patentable innovations related to rocketry, as well as receiving U.S. patents after the war concerning the advancement of rocketry. Documented accounts also stated he provided solutions to a host of aerospace engineering problems in the 1950s and 1960s.

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

ordered the production of the A-4 as a "vengeance weapon", and the Peenemünde group developed it to target London. Following von Braun's 7 July 1943 presentation of a color movie showing an A-4 taking off, Hitler was so enthusiastic that he personally made von Braun a professor shortly thereafter.

By that time, the British and Soviet intelligence

This is a list of historical secret police organizations. In most cases they are no longer current because the regime that ran them was overthrown or changed, or they changed their names. Few still exist under the same name as legitimate police fo ...

agencies were aware of the rocket program and von Braun's team at Peenemünde, based on the intelligence provided by the Polish underground Home Army

The Home Army ( pl, Armia Krajowa, abbreviated AK; ) was the dominant resistance movement in German-occupied Poland during World War II. The Home Army was formed in February 1942 from the earlier Związek Walki Zbrojnej (Armed Resistance) esta ...

. Over the nights of 17–18 August 1943, RAF Bomber Command

RAF Bomber Command controlled the Royal Air Force's bomber forces from 1936 to 1968. Along with the United States Army Air Forces, it played the central role in the strategic bombing of Germany in World War II. From 1942 onward, the British bo ...

's Operation Hydra dispatched raids on the Peenemünde camp consisting of 596 aircraft, and dropped 1,800 tons of explosives. The facility was salvaged and most of the engineering team remained unharmed; however, the raids killed von Braun's engine designer Walter Thiel

Walter Thiel (3 March 1910, Breslau – 17 August 1943, Karlshagen, near Peenemünde) was a German rocket scientist.

Thiel provided the decisive ideas for the A4 (V-2) rocket engine and his research enabled rockets to head towards space.

Lif ...

and Chief Engineer Walther, and the rocket program was delayed.

The first combat A-4, renamed the V-2

The V-2 (german: Vergeltungswaffe 2, lit=Retaliation Weapon 2), with the technical name ''Aggregat 4'' (A-4), was the world’s first long-range guided ballistic missile. The missile, powered by a liquid-propellant rocket engine, was develope ...

(''Vergeltungswaffe 2'' "Retaliation/Vengeance Weapon 2") for propaganda purposes, was launched toward England on 7 September 1944, only 21 months after the project had been officially commissioned.

Experiments with rocket aircraft

During 1936, von Braun's rocketry team working at Kummersdorf investigated installing liquid-fuelled rockets in aircraft.Ernst Heinkel

Dr. Ernst Heinkel (24 January 1888 – 30 January 1958) was a German aircraft designer, manufacturer, ''Wehrwirtschaftsführer'' in Nazi Germany, and member of the Nazi party. His company Heinkel Flugzeugwerke produced the Heinkel He 178, th ...

enthusiastically supported their efforts, supplying a He-72 and later two He-112s for the experiments. Later in 1936, Erich Warsitz

Erich Warsitz (18 October 1906, Hattingen, Westphalia – 12 July 1983) was a German test pilot of the 1930s. He held the rank of Flight-Captain in the Luftwaffe and was selected by the Reich Air Ministry as chief test pilot at Peenemünde We ...

was seconded by the RLM to von Braun and Heinkel, because he had been recognized as one of the most experienced test pilots of the time, and because he also had an extraordinary fund of technical knowledge. After he familiarized Warsitz with a test-stand run, showing him the corresponding apparatus in the aircraft, he asked: "Are you with us and will you test the rocket in the air? Then, Warsitz, you will be a famous man. And later we will fly to the Moon – with you at the helm!"

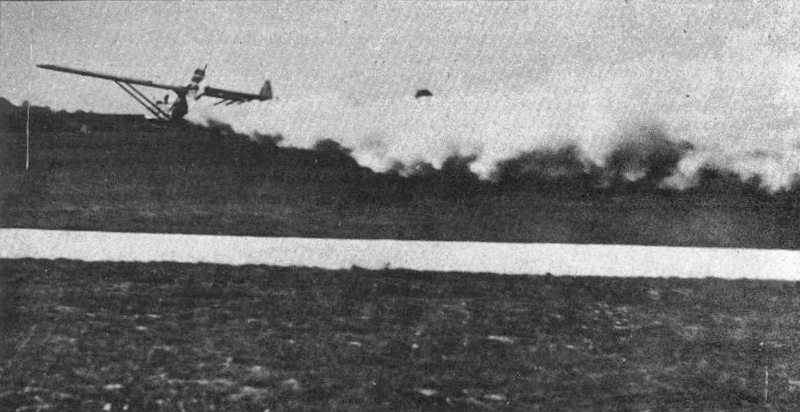

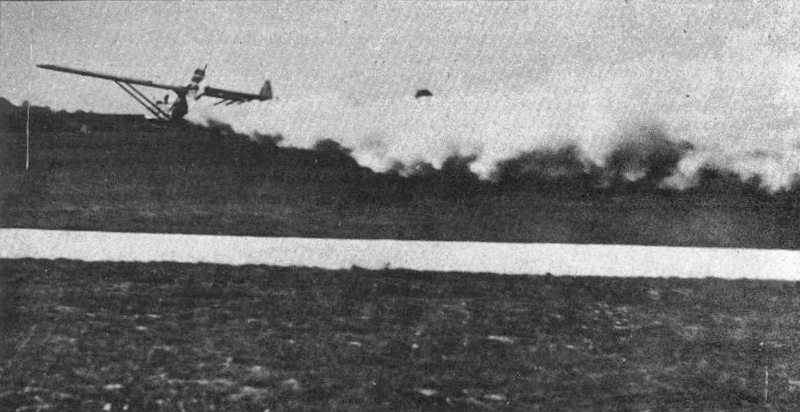

In June 1937, at

In June 1937, at Neuhardenberg

Neuhardenberg is a municipality in the district Märkisch-Oderland, in Brandenburg, Germany. It is the site of Neuhardenberg Palace, residence of the Prussian statesman Prince Karl August von Hardenberg (1750-1822). The municipal area comprises th ...

(a large field about east of Berlin, listed as a reserve airfield in the event of war), one of these latter aircraft was flown with its piston engine

A reciprocating engine, also often known as a piston engine, is typically a heat engine that uses one or more reciprocating pistons to convert high temperature and high pressure into a rotating motion. This article describes the common featu ...

shut down during flight by Warsitz, at which time it was propelled by von Braun's rocket power alone. Despite a wheels-up landing and the fuselage having been on fire, it proved to official circles that an aircraft could be flown satisfactorily with a back-thrust system through the rear.

At the same time, Hellmuth Walter

Hellmuth Walter (26 August 1900 – 16 December 1980) was a German engineer who pioneered research into rocket engines and gas turbines. His most noteworthy contributions were rocket motors for the Messerschmitt Me 163 and Bachem Ba 349 intercept ...

's experiments into hydrogen peroxide

Hydrogen peroxide is a chemical compound with the formula . In its pure form, it is a very pale blue liquid that is slightly more viscous than water. It is used as an oxidizer, bleaching agent, and antiseptic, usually as a dilute solution (3%� ...

based rockets were leading towards light and simple rockets that appeared well-suited for aircraft installation. Also the firm of Hellmuth Walter at Kiel had been commissioned by the RLM to build a rocket engine for the He-112, so there were two different new rocket motor designs at Neuhardenberg: whereas von Braun's engines were powered by alcohol and liquid oxygen, Walter engines had hydrogen peroxide and calcium permanganate

Calcium permanganate is an oxidizing agent and chemical compound with the chemical formula Ca(MnO4)2. This salt consists of the metal calcium and two permanganate ions.

Preparation

The salt is prepared from the reaction of potassium permanganat ...

as a catalyst

Catalysis () is the process of increasing the rate of a chemical reaction by adding a substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed in the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recyc ...

. Von Braun's engines used direct combustion and created fire, the Walter devices used hot vapors from a chemical reaction, but both created thrust and provided high speed. The subsequent flights with the He-112 used the Walter-rocket instead of von Braun's; it was more reliable, simpler to operate, and safer for the test pilot, Warsitz.

Slave labor

SS GeneralHans Kammler

Hans Kammler (26 August 1901 – 1945 ssumed was an SS-Obergruppenführer responsible for Nazi civil engineering projects and its top secret weapons programmes. He oversaw the construction of various Nazi concentration camps before being put ...

, who as an engineer had constructed several concentration camp

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

s, including Auschwitz

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) during World War II and the Holocaust. It con ...

, had a reputation for brutality and had originated the idea of using concentration camp prisoners as slave laborers in the rocket program. Arthur Rudolph

Arthur Louis Hugo Rudolph (November 9, 1906 – January 1, 1996) was a German rocket engineer who was a leader of the effort to develop the V-2 rocket for Nazi Germany. After World War II, the United States Government's Office of Strategic Servic ...

, chief engineer of the V-2 rocket factory at Peenemünde, endorsed this idea in April 1943 when a labor shortage developed. More people died building the V-2 rockets than were killed by it as a weapon. Von Braun admitted visiting the plant at Mittelwerk

Mittelwerk (; German for "Central Works") was a German World War II factory built underground in the Kohnstein to avoid Allied bombing. It used slave labor from the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp to produce V-2 ballistic missiles, V-1 flyin ...

on many occasions, and called conditions at the plant "repulsive", but claimed never to have personally witnessed any deaths or beatings, although it had become clear to him by 1944 that deaths had occurred. He denied ever having visited the Mittelbau-Dora

Mittelbau-Dora (also Dora-Mittelbau and Nordhausen-Dora) was a Nazi concentration camp located near Nordhausen in Thuringia, Germany. It was established in late summer 1943 as a subcamp of Buchenwald concentration camp, supplying slave labour ...

concentration camp itself, where 20,000 died from illness, beatings, hangings, and intolerable working conditions.

Some prisoners claim von Braun engaged in brutal treatment or approved of it. Guy Morand, a French resistance fighter who was a prisoner in Dora, testified in 1995 that, after an apparent sabotage attempt, von Braun ordered a prisoner to be flogged, while Robert Cazabonne, another French prisoner, claimed von Braun stood by as prisoners were hanged by chains suspended by cranes. However, these accounts may have been a case of mistaken identity. Former Buchenwald

Buchenwald (; literally 'beech forest') was a Nazi concentration camp established on hill near Weimar, Germany, in July 1937. It was one of the first and the largest of the concentration camps within Germany's 1937 borders. Many actual or su ...

inmate Adam Cabala claims that von Braun went to the concentration camp to pick slave laborers:

... also the German scientists led by Prof. Wernher von Braun were aware of everything daily. As they went along the corridors, they saw the exhaustion of the inmates, their arduous work and their pain. Not one single time did Prof. Wernher von Braun protest against this cruelty during his frequent stays at Dora. Even the aspect of corpses did not touch him: On a small area near the ambulance shed, inmates tortured to death by slave labor and the terror of the overseers were piling up daily. But, Prof. Wernher von Braun passed them so close that he was almost touching the corpses.Von Braun later claimed that he was aware of the treatment of prisoners, but felt helpless to change the situation.

Arrest and release by the Nazi regime

According to André Sellier, a French historian and survivor of theMittelbau-Dora

Mittelbau-Dora (also Dora-Mittelbau and Nordhausen-Dora) was a Nazi concentration camp located near Nordhausen in Thuringia, Germany. It was established in late summer 1943 as a subcamp of Buchenwald concentration camp, supplying slave labour ...

concentration camp, Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

had von Braun come to his Feldkommandostelle Hochwald HQ in East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label=Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 187 ...

in February 1944. To increase his power-base within the Nazi regime, Himmler was conspiring to use Kammler to gain control of all German armament programs, including the V-2 program at Peenemünde. He therefore recommended that von Braun work more closely with Kammler to solve the problems of the V-2. Von Braun claimed to have replied that the problems were merely technical and he was confident that they would be solved with Dornberger's assistance.

Von Braun had been under SD surveillance since October 1943. A secret report stated that he and his colleagues Klaus Riedel

Klaus Riedel (2 August 1907 – 4 August 1944) was a German rocket pioneer. He was involved in many early liquid-fuelled rocket experiments, and eventually worked on the V-2 missile programme at Peenemünde Army Research Center.

History

Ried ...

and Helmut Gröttrup

Helmut Gröttrup (12 February 1916 – 4 July 1981) was a German engineer, rocket scientist and inventor of the smart card. During World War II, he worked in the German V-2 rocket program under Wernher von Braun. From 1946 to 1950 he headed a grou ...

were said to have expressed regret at an engineer's house one evening in early March 1944 that they were not working on a spaceship and that they felt the war was not going well; this was considered a "defeatist" attitude. A young female dentist who was an SS spy reported their comments. Combined with Himmler's false charges that von Braun and his colleagues were communist sympathizers and had attempted to sabotage the V-2 program, and considering that von Braun regularly piloted his government-provided airplane that might allow him to escape to Britain, this led to their arrest by the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one organi ...

.

The unsuspecting von Braun was detained on 14 March (or 15 March), 1944, and was taken to a Gestapo cell in Stettin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin language, Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital city, capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the Po ...

(now Szczecin, Poland). where he was held for two weeks without knowing the charges against him.

Through Major Hans Georg Klamroth

Johannes "Hans" Georg Klamroth (12 October 1898, Halberstadt – 26 August 1944) was, by his knowledge of the plans through distant relatives and his son-in-law Lieutenant-Colonel , involved in the 20 July plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler.

After t ...

, in charge of the Abwehr

The ''Abwehr'' (German for ''resistance'' or ''defence'', but the word usually means ''counterintelligence'' in a military context; ) was the German military-intelligence service for the ''Reichswehr'' and the ''Wehrmacht'' from 1920 to 1944. A ...

for Peenemünde, Dornberger obtained von Braun's conditional release and Albert Speer

Berthold Konrad Hermann Albert Speer (; ; 19 March 1905 – 1 September 1981) was a German architect who served as the Minister of Armaments and War Production in Nazi Germany during most of World War II. A close ally of Adolf Hitler, he ...

, Reichsminister for Munitions and War Production, persuaded Hitler to reinstate von Braun so that the V-2 program could continue or turn into a "V-4 program" (the Rheinbote

''Rheinbote'' (''Rhine Messenger'', or V4) was a German short range ballistic rocket developed by Rheinmetall-Borsig at Berlin-Marienfelde during World War II. It was intended to replace, or at least supplement, large-bore artillery by providing f ...

as a short range ballistic rocket) which in their view would be impossible without von Braun's leadership.Ward, Bob. 2013. ''Dr. Space: The Life of Wernher von Braun''. Naval Institute Press. Ch. 5 In his memoirs, Speer states Hitler had finally conceded that von Braun was to be "protected from all prosecution as long as he is indispensable, difficult though the general consequences arising from the situation."

Upon investigation by the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation on 1 May 1961 advised that “there was no record of an arrest in their respective files” suggesting that Von Braun’s imprisonment was wiped from German prison records at a point after his conditional release or after the Nazi regime had fallen.

Surrender to the Americans

The

The Soviet Army

uk, Радянська армія

, image = File:Communist star with golden border and red rims.svg

, alt =

, caption = Emblem of the Soviet Army

, start_date ...

was about from Peenemünde in early 1945 when von Braun assembled his planning staff and asked them to decide how and to whom they should surrender. Unwilling to go to the Soviets, von Braun and his staff decided to try to surrender to the Americans. Kammler had ordered relocation of his team to central Germany; however, a conflicting order from an army chief ordered them to join the army and fight. Deciding that Kammler's order was their best bet to defect to the Americans, von Braun fabricated documents and transported 500 of his affiliates to the area around Mittelwerk, where they resumed their work in Bleicherode

Bleicherode () is a town in the district of Nordhausen, in Thuringia, Germany. It is situated on the river Wipper, 17 km southwest of Nordhausen. On 1 December 2007, the former municipality Obergebra was incorporated by Bleicherode. The for ...

and surrounding towns after the middle of February 1945. For fear of their documents being destroyed by the SS, von Braun ordered the blueprints to be hidden in an abandoned iron mine in the Harz

The Harz () is a highland area in northern Germany. It has the highest elevations for that region, and its rugged terrain extends across parts of Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Thuringia. The name ''Harz'' derives from the Middle High German ...

mountain range near Goslar

Goslar (; Eastphalian: ''Goslär'') is a historic town in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is the administrative centre of the district of Goslar and located on the northwestern slopes of the Harz mountain range. The Old Town of Goslar and the Mines ...

. The US Counterintelligence Corps

The Counter Intelligence Corps (Army CIC) was a World War II and early Cold War intelligence agency within the United States Army consisting of highly trained special agents. Its role was taken over by the U.S. Army Intelligence Corps in 1961 and ...

managed to unveil the location after lengthy interrogations of von Braun, Walter Dornberger, Bernhard Tessmann

Bernhard Robert Tessmann (August 15, 1912 in Zingst – December 19, 1998) was a German expert in guided missiles during World War II, and later worked for the United States Army and NASA.

Life

Tessmann first met rocket expert Wernher von Braun i ...

and Dieter Huzel and recovered 14 tons of V-2 documents by 15 May 1945, from the British Occupation Zone

The British occupation zone in Germany (German: ''Britische Besatzungszone Deutschlands'') was one of the Allied-occupied areas in Germany after World War II. The United Kingdom along with her Commonwealth were one of the three major Allied pow ...

.

While on an official trip in March, von Braun suffered a complicated fracture of his left arm and shoulder in a car accident after his driver fell asleep at the wheel. His injuries were serious, but he insisted that his arm be set in a cast so he could leave the hospital. Due to this neglect of the injury he had to be hospitalized again a month later when his bones had to be rebroken and realigned.

In early April, as the Allied forces advanced deeper into Germany, Kammler ordered the engineering team, around 450 specialists, to be moved by train into the town of Oberammergau

Oberammergau is a municipality in the district of Garmisch-Partenkirchen, in Bavaria, Germany. The small town on the Ammer River is known for its woodcarvers and woodcarvings, for its NATO School, and around the world for its 380-year tradition of ...

in the Bavarian Alps

The Bavarian Alps (german: Bayerische Alpen) is a collective name for several mountain ranges of the Northern Limestone Alps within the German state of Bavaria.

Geography

The term in its wider sense refers to that part of the Eastern Alps that ...

, where they were closely guarded by the SS with orders to execute the team if they were about to fall into enemy hands. However, von Braun managed to convince SS Major Kummer to order the dispersal of the group into nearby villages so that they would not be an easy target for U.S. bombers. On 29 April 1945, Oberammergau was captured by the Allied forces who seized the majority of the engineering team.

Nearing the end of the war, Hitler had instructed SS troops to gas all technical men concerned with rocket development. Upon hearing this, Von Braun commandeered a train, and fled with other “technical men” to a location in the mountains of South Germany. After some time, Von Braun and many of the others who made it to the mountains left their location to flee to advancing American lines in Austria.

Von Braun and several members of the engineering team, including Dornberger, made it to Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

. On 2 May 1945, upon finding an American private from the U.S. 44th Infantry Division, von Braun's brother and fellow rocket engineer, Magnus, approached the soldier on a bicycle, calling out in broken English: "My name is Magnus von Braun. My brother invented the V-2. We want to surrender." After the surrender, Wernher von Braun spoke to the press:

We knew that we had created a new means of warfare, and the question as to what nation, to what victorious nation we were willing to entrust this brainchild of ours was a moral decision more than anything else. We wanted to see the world spared another conflict such as Germany had just been through, and we felt that only by surrendering such a weapon to people who are guided not by the laws of materialism but by Christianity and humanity could such an assurance to the world be best secured.The American high command was well aware of how important their catch was: von Braun had been at the top of the ''Black List'', the code name for the list of German scientists and engineers targeted for immediate interrogation by U.S. military experts. On 9 June 1945, two days before the originally scheduled handover of the

Nordhausen Nordhausen may refer to:

* Nordhausen (district), a district in Thuringia, Germany

** Nordhausen, Thuringia, a city in the district

**Nordhausen station, the railway station in the city

* Nordhouse, a commune in Alsace (German: Nordhausen)

* Narost ...

and Bleicherode area in Thuringia

Thuringia (; german: Thüringen ), officially the Free State of Thuringia ( ), is a state of central Germany, covering , the sixth smallest of the sixteen German states. It has a population of about 2.1 million.

Erfurt is the capital and larg ...

to the Soviets, U.S. Army Major Robert B. Staver, Chief of the Jet Propulsion Section of the Research and Intelligence Branch of the U.S. Army Ordnance Corps in London, and Lieutenant Colonel R. L. Williams took von Braun and his department chiefs by Jeep from Garmisch to Munich, from where they were flown to Nordhausen. In the following days, a larger group of rocket engineers, among them Helmut Gröttrup, was evacuated from Bleicherode southwest to Witzenhausen

Witzenhausen is a small town in the Werra-Meißner-Kreis in northeastern Hesse, Germany.

It was granted town rights in 1225, and until 1974, it was a district seat.

The University of Kassel maintains a satellite campus in Witzenhausen at which is ...

, a small town in the American Zone

Germany was already de facto occupied by the Allies from the real fall of Nazi Germany in World War II on 8 May 1945 to the establishment of the East Germany on 7 October 1949. The Allies (United States, United Kingdom, Soviet Union, and Franc ...

.

Von Braun was briefly detained at the "Dustbin" interrogation center at Kransberg Castle

Kransberg Castle is situated on a steep rock near Kransberg (incorporated into Usingen in 1971), a village with about 800 inhabitants in the Taunus mountains in the German state of Hesse. The medieval building, which acquired its current appearan ...

, where the elite of Nazi Germany's economic, scientific and technological sectors were debriefed by U.S. and British intelligence officials. Initially, he was recruited to the U.S. under a program called Operation Overcast, subsequently known as Operation Paperclip

Operation Paperclip was a secret United States intelligence program in which more than 1,600 German scientists, engineers, and technicians were taken from the former Nazi Germany to the U.S. for government employment after the end of World War ...

. There is evidence, however, that British intelligence and scientists were the first to interview him in depth, eager to gain information that they knew U.S. officials would deny them. The team included the young L.S. Snell, then the leading British rocket engineer, later chief designer of Rolls-Royce Limited

Rolls-Royce was a British luxury car and later an aero-engine manufacturing business established in 1904 in Manchester by the partnership of Charles Rolls and Henry Royce. Building on Royce's good reputation established with his cranes, they ...

and inventor of the Concorde

The Aérospatiale/BAC Concorde () is a retired Franco-British supersonic airliner jointly developed and manufactured by Sud Aviation (later Aérospatiale) and the British Aircraft Corporation (BAC).

Studies started in 1954, and France an ...

's engines. The specific information the British gleaned remained top secret, both from the Americans and from the other allies.

American career

U.S. Army career

On 20 June 1945,

On 20 June 1945, U.S. Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State. The office holder is one of the highest ranking members of the president's Ca ...

Edward Stettinius Jr. approved the transfer of von Braun and his specialists to the United States as one of his last acts in office; however, this was not announced to the public until 1 October 1945.

The first seven technicians arrived in the United States at New Castle Army Air Field

New Castle National Guard Base is a United States Air Force installation under the control of the Delaware Air National Guard, located at New Castle Airport in New Castle County, Delaware.

Overview

The base is the home of the 166th Airlift Wi ...

, just south of Wilmington, Delaware

Wilmington ( Lenape: ''Paxahakink /'' ''Pakehakink)'' is the largest city in the U.S. state of Delaware. The city was built on the site of Fort Christina, the first Swedish settlement in North America. It lies at the confluence of the Christina ...

, on 20 September 1945. They were then flown to Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

, and taken by boat to the Army Intelligence Service post at Fort Strong

Fort Strong is a former U.S. Army Coast Artillery fort that occupied the northern third of Long Island in Boston Harbor. The island had a training camp during the American Civil War, and a gun battery was built there in the 1870s. The fort was ...

in Boston Harbor

Boston Harbor is a natural harbor and estuary of Massachusetts Bay, and is located adjacent to the city of Boston, Massachusetts. It is home to the Port of Boston, a major shipping facility in the northeastern United States.

History

Since ...

. Later, with the exception of von Braun, the men were transferred to Aberdeen Proving Ground

Aberdeen Proving Ground (APG) (sometimes erroneously called Aberdeen Proving ''Grounds'') is a U.S. Army facility located adjacent to Aberdeen, Harford County, Maryland, United States. More than 7,500 civilians and 5,000 military personnel work at ...

in Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

to sort out the Peenemünde documents, enabling the scientists to continue their rocketry experiments.

Finally, von Braun and his remaining Peenemünde staff (see List of German rocket scientists in the United States

The following lists contain names of engineers, scientists and technicians specializing in rocketry who originally came from Germany but spent most of their careers working for the NASA space program in Huntsville, Alabama.

Particularly after Worl ...

) were transferred to their new home at Fort Bliss

Fort Bliss is a United States Army post in New Mexico and Texas, with its headquarters in El Paso, Texas. Named in honor of William Wallace Smith Bliss, LTC William Bliss (1815–1853), a mathematics professor who was the son-in-law of President ...

, a large Army installation just north of El Paso, Texas

El Paso (; "the pass") is a city in and the county seat, seat of El Paso County, Texas, El Paso County in the western corner of the U.S. state of Texas. The 2020 population of the city from the United States Census Bureau, U.S. Census Bureau w ...

. Von Braun later wrote that he found it hard to develop a "genuine emotional attachment" to his new surroundings.Matthew Brzezinski (2007''Red Moon Rising: Sputnik and the Hidden Rivalries That Ignited the Space Age''

pages 84–92, Henry Holt, New York His chief design engineer Walther Reidel became the subject of a December 1946 article "German Scientist Says American Cooking Tasteless; Dislikes Rubberized Chicken", exposing the presence of von Braun's team in the country and drawing criticism from

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theory ...

and John Dingell

John David Dingell Jr. (July 8, 1926 – February 7, 2019) was an American politician who served as a member of the United States House of Representatives from 1955 until 2015. A member of the Democratic Party, he holds the record for longest ...

. Requests to improve their living conditions such as laying linoleum over their cracked wood flooring were rejected. Von Braun was hypercritical of the slowness of the United States development of guided missiles. His lab was never able to get sufficient funds to go on with their programs. Von Braun remarked, "at Peenemünde we had been coddled, here you were counting pennies". Whereas von Braun had thousands of engineers who answered to him at Peenemünde, he was now subordinate to "pimply" 26-year-old Jim Hamill, an Army major who possessed only an undergraduate degree in engineering. His loyal Germans still addressed him as "Herr Professor," but Hamill addressed him as "Wernher" and never responded to von Braun's request for more materials. Every proposal for new rocket ideas was dismissed.

While at Fort Bliss, they trained military, industrial, and university personnel in the intricacies of rockets and guided missiles. As part of the

While at Fort Bliss, they trained military, industrial, and university personnel in the intricacies of rockets and guided missiles. As part of the Hermes project